This is an old version of the Geoism Blueprint article. While the author stands by it, it proved cumbersome for most readers. It also jumped straight to solutions without discussing their implementation. Check out the newest Geoism Blueprint article, which is much more refined.

Introduction

Mother Earth is not a stock market. Treating her as such creates a real-life game of Monopoly, with exaggerated income inequality, barely livable minimum wages, and ever-increasing rents. This can be seen in cities like San Francisco, where homeless masses eke out an existence alongside billionaires and their mansions. The crisis was predicted over a hundred and forty years ago:

If there is less deep poverty in San Fran Francisco than in New York, is it not because San Francisco is yet behind new York in all that both cities are striving for? When San Francisco reaches the point where New York now is, who can doubt that there will also be ragged and barefooted children on her streets?

Henry George, Progress and Poverty

In the late 1800s, an economist named Henry George noticed issues of poverty in industrial societies, and set out to find the cause and solution. His work would inspire a woman named Lizzie Magie to create a board game, to teach his theories to the wider public. That board game would later be plagiarized as Monopoly. Monopoly still illustrates some of the problems Henry George was trying to solve. Unlike Lizzie Magie’s “The Landlord’s Game®,” however, it doesn’t reveal his solution.

Would you like to see his solution?

Author’s Note

The following is an attempt to explain Georgism (Aka “Geoism”) as simply as possible, while retaining its core message. To more deeply understand Georgism, the author highly recommends following it up with Lars Doucet’s articles on Georgism, or, better yet, with the book that inspired the movement to begin with, Henry George’s “Progress and Poverty.”

Lizzie Magie’s invention, “The Landlord’s Game®,” is also an excellent resource for understanding Georgism.

Laying Some Groundwork

Defining The Problem

Before revealing solutions, it’s important to clarify the problem that’s being solved. In this case, the problem is this (Taken shamelessly from Lars Doucet’s article):

Poverty and wealth disparity appear to be perversely linked with progress.

Defining Land

Land, as the term is used in this article, and by Henry George, refers to nature, and location. A plot of grass is land, a pond is land, and a city block is land. The city block’s buildings (properties) are not land, but the location of the block, and the earth on which it sits, is land.

Land is necessary for any and all types of labor. Try doing literally anything without a location. You can’t, unless you plan to transcend the physical plane. Try acquiring any materials that didn’t originate from nature at some point. You’d have to go to outer space (In the future, space might also be considered land).

This definition will be extremely important in understanding the solution to the problem presented.

Land Rent

The problem and its solution will be illustrated through story. To understand the story, it’s important to understand one economic principle in particular: Ricardo’s Law of Rent. Don’t worry, it’s not complicated.

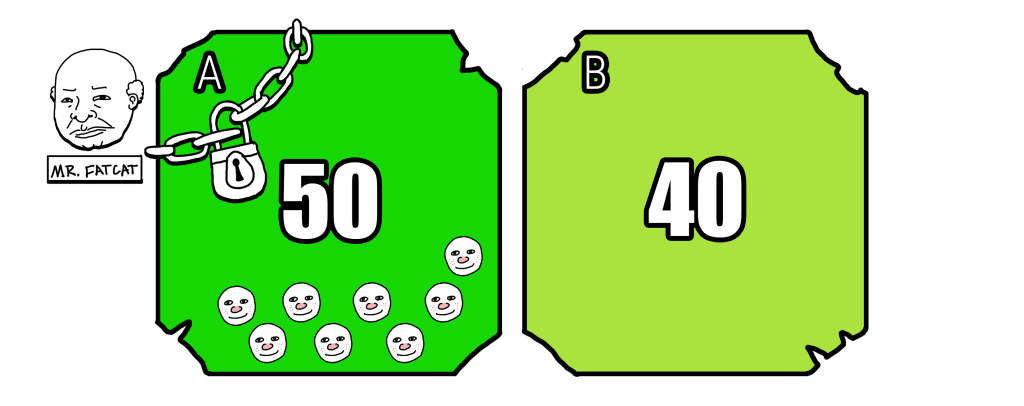

Ricardo’s law of rent basically states that the rent of a land site is equal to that site’s economic value minus the most valuable rent-free land available. You can simplify it as:

Land Rent = Land Value – Best Unowned Land Value

So, in the above example, if land A is worth 50 units, and the best unowned land (Land B) is worth 40 units, then land rent for land A is: 50 – 40, or 10 units. If rent were higher than 10 in the above example, the earnings from land A would be less than land B, and a reasonable person would just work land B instead.

Property Rent

What about rent for a house, apartment, or office? When separated from land rents, property rents are compensation for maintenance, utilities, etc. The material costs of actually building the property in the first place are priced in there, too. To sum it up, property rents in this article basically refers to compensation for capital investment and labor.

Given two properties that are physically the same, their property rents will pretty much be the same. Think about it: the materials and labor involved in building and maintaining properties (Again, the buildings, not the land) do not change dramatically from land plot to land plot. It’s the land itself that drives cost differences.

Total Rent

Total rent = land rent + property rent

Welcome To Boxville

Humble Beginnings

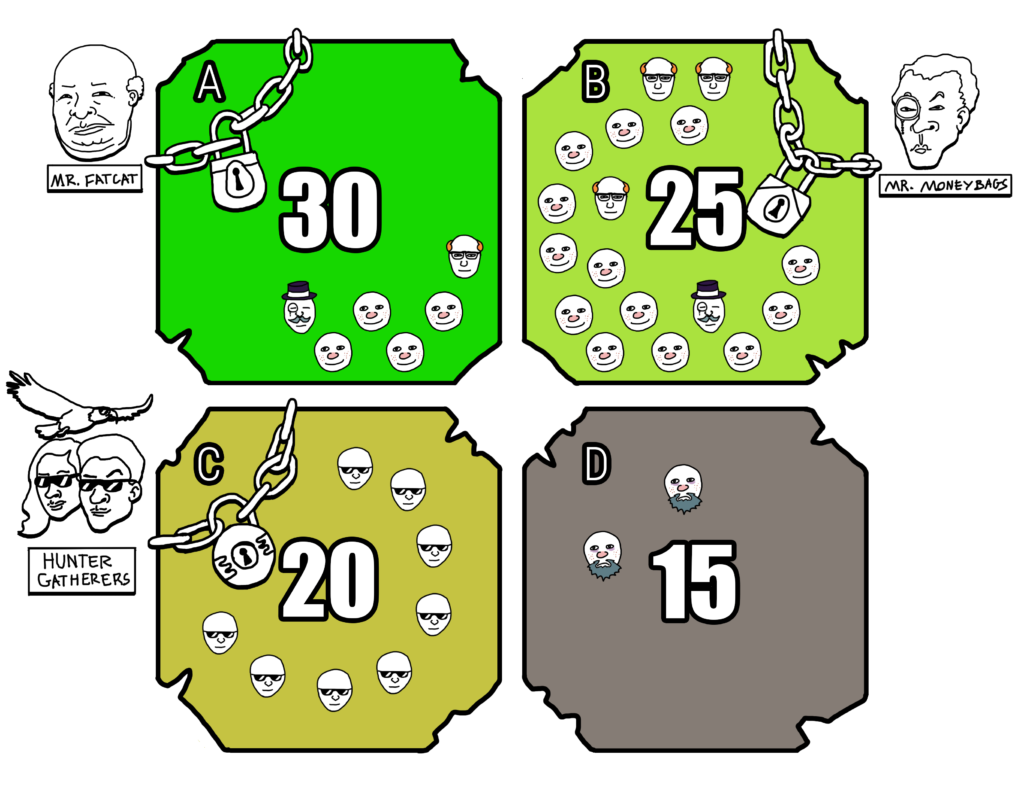

Boxville is a remote city, split into four parts. The most valuable part is land A, a fertile land. Each plot of land in land A is capable of producing 20 whole units of value per month. Plots in land B, C, and D produce 15, 10, and 5 units of value per month, respectively. All of land A is owned by Mr. Fatcat, an absentee landlord who has never even visited Boxville. Land B consists of a loose collection of neighborhoods, apartments, businesses, and a few unowned plots.

The property rent for a baseline living space (A studio apartment) in Boxville is 5 units per month. This is the most affordable form of housing available.

A few villagers live on plots in land A, but most of A sits empty. They each pay Mr. Fatcat 5 units of land rent per month, per plot. That’s the value of land A plots (20 units per month, per plot), minus the best unowned land value (15 units per month, per plot). They also pay him 5 units of property rent at a minimum per month, per adult household. The villagers in plot B pay their landlords 0 units of land rent per month (15 – 15 = 0), and 5 units of property rent.

Unowned plots are claimed by the city, but for all intents and purposes, they are not regulated. Lands C and D are occupied by a few hunter-gatherers, who pay no land rent (As the lands are not private property), but rather keep the fruits of their labor.

Three Forms Of Progress

Boxville will be visited by the three forms of material progress: technological advances, improvements in social fabric, and increased population. This progress will bring much wealth to the town, but rather than being a net blessing, it will also bring poverty and wealth disparity to the once peaceful community. Let’s see how this happens.

Technological Advances

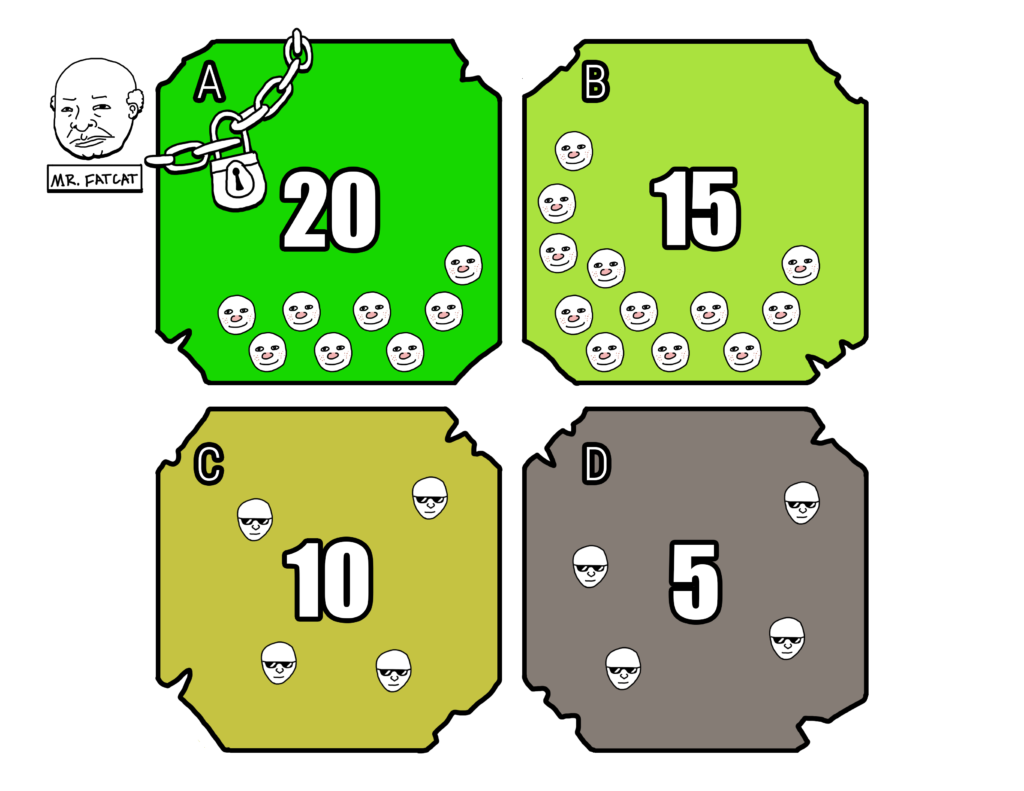

Major technological advances make it possible to acquire more resources from each plot of land. With the right equipment, they can now each produce 5 additional units of value per plot, per month! Seeing the increased value of the plots, a speculator named Mr. Moneybags (Who has never visited Boxville, and never will) buys the entirety of land B, including the unowned plots. He is now the town’s second absentee landlord.

Investors bring their businesses, along with their tools and equipment, to lands A and B, allowing their additional resources to be harvested. More villagers also arrive, eager to take part in the new industry. Both new and old residents pay rent to Mr. Fatcat, or Mr. Moneybags, depending on the plot.

Let’s see how the situation in Boxville has changed:

Remember Ricardo’s Law of Rent?

Land rent for land A is now 10 units per plot (25 – 15 = 10). Land rent for land B is 5 units per plot (20 – 15 = 5). Add 5 units of property rent to those numbers for the baseline total rent. Notice how the rent got more expensive for the villagers? Even though the land got more productive for everybody, the end result was that rent got more expensive for the villagers, while the absentee landlords’ net worth increased, as did their rental income.

Several residents of land A move, as they cannot afford the higher rent. Mr. Fatcat simply lets their residences rot (Property taxes are lower that way), and continues sitting on many empty plots in land A. While someone could build affordable housing (Say, apartments) on the empty or rotting lots, Mr. Fatcat would rather wait for the land to become more valuable before selling it. Existing residents of land B also feel the stress of higher rent.

Improvements in Social Fabric

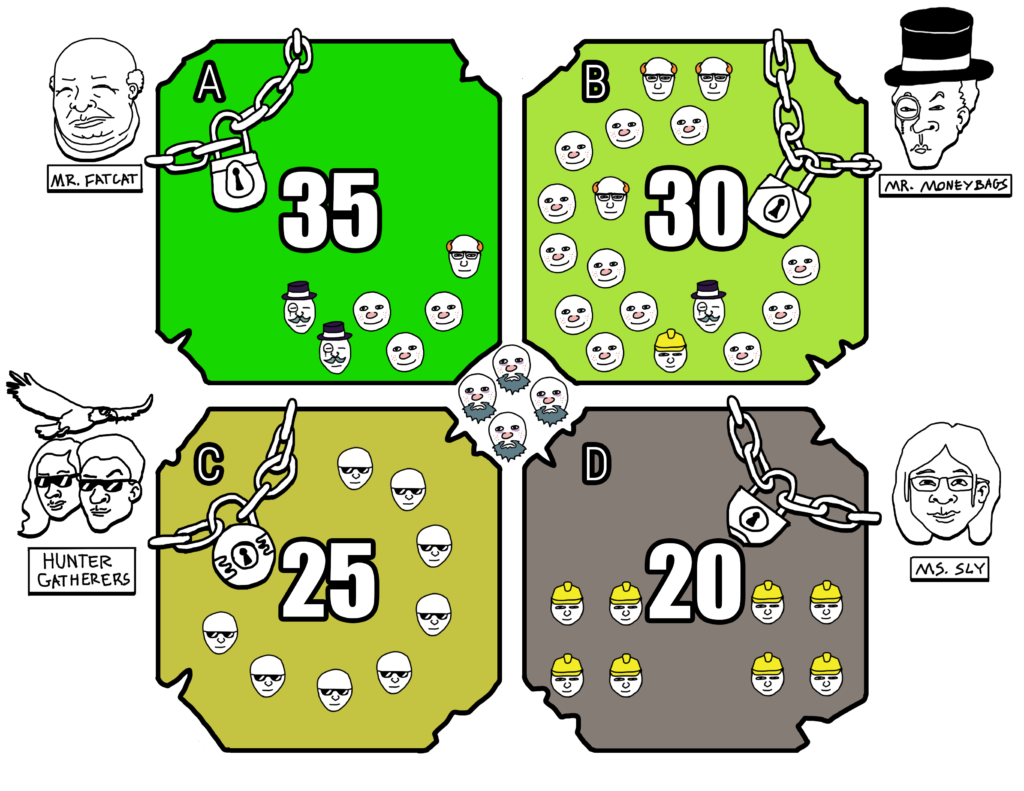

The hunter-gatherers, like certain other historic societies, do not view land ownership in the same manner as their neighbors. Concerned that their way of life may be threatened, several of them band together and collectively buy land C. Any rent that is paid to them is immediately invested back into their community. Working together, they foster a vibrant culture that infuses all of Boxville with a renewed sense of creativity, vigor, and kinship.

Their strategy is so successful that land C, and all surrounding lands increase in value by 5 units per plot.

This is the new land situation in Boxville:

Land rent for land A is now 15 units per plot (30 – 15 = 15; you get the gist). Land rent for land B is now 10 units per plot, and land rent for land C is 5 units per plot. Again, add 5 units of property rent for the baseline total rent. The total rent costs are higher for everybody! While society has improved so much that all of Boxville’s lands are more valuable, the end result is, again, higher rent. Mr. Fatcat and Mr. Moneybags, on the other hand, made money without lifting a finger.

Much of land A still sits tragically idle, even as residents from both land A and B struggle to keep up with increased rents. A handful of wealthy newcomers enter town to live in lands A and B. The poorest residents, unable to pay the higher rent, leave town, or become homeless.

Increased Population

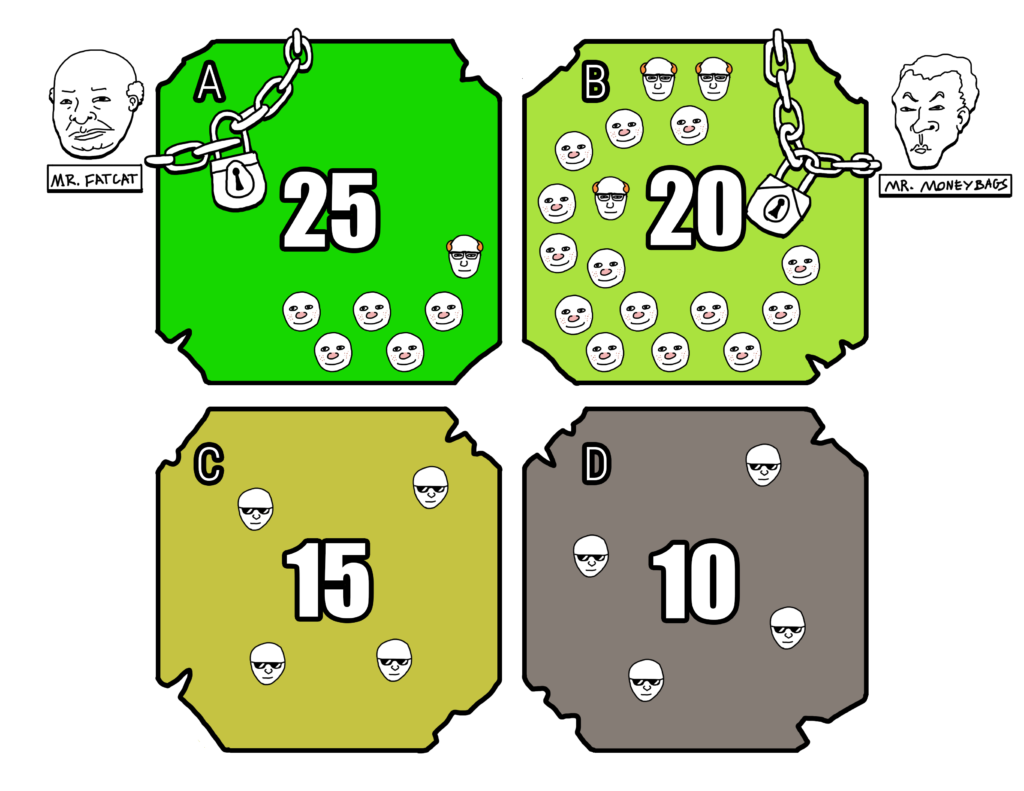

Seeing how much Boxville is growing, a shrewd investor named Ms. Sly purchases land D. Working with a team of contractors and builders, she constructs as much affordable housing and infrastructure as she can. She’s a diligent worker, ensuring that her housing is kept in top shape. This brings in a flood of new workers to Boxville. These newcomers’ valuable labor and services increase the productive capacity of the town’s lands by another 5 units per plot.

The land situation in Boxville now looks like this:

Hold on a second, there are no unowned lands anymore. How do we calculate rent?

Minimum Wage

When all land (Without which it is impossible to perform labor) has been monopolized, land rent is theoretically 100%. In reality, no one will pay 100% of their land’s productive value in rent, if that amount will leave them starving to death. Good luck squeezing rent out of a corpse.

Having rent values that are arbitrarily high means that land owners can simply push rent up (and by extension, wages down) as far as people will tolerate. Here’s how Henry George put it:

The reason why, in spite of increase of productive power, wages constantly tend to a minimum which will give but a bare living, is that, with increase in productive power, rent tends to even greater increase, thus producing a constant tendency to the forcing down of wages.

Henry George, Progress and Poverty

Wages to a minimum … minimum wage. Sound familiar? Land rent is the root of the minimum wage problem, where wages stagnate to the point that they can barely cover cost of living expenses.

Aftermath For Boxville

Rent in land A is too expensive for most people. Despite the incredible value of the land, most of its plots sit vacant or rotting. Rumor has it that Mr. Fatcat plans to cash out in a few decades. He’ll make a hefty sum of money, as the land is almost twice as valuable as it once was. Mr. Fatcat barely lifted a single finger for Boxville, but Boxville sure made him rich!

Rent in land B is manageable for some of the wealthier members of Boxville society. Mr. Moneybags collects a nice sum of total rent from the land’s residents, and his net worth has skyrocketed with the increasing value of the land. All he had to do was write a few checks, sit back, and collect the villagers’ earnings!

The former hunter-gatherers of land C are okay. Everything around them is getting more expensive, though, as prices increase to reflect higher costs of living. Many in land C realize that they could, like the absentee landlords, just keep all the rent paid to them and rake in a tidy sum of money each month (Instead of investing it back into their community). Although this would betray their core values, they have economic incentive to do so.

Land D is quite profitable. For now, Ms. Sly does provide valuable services to her tenants, as she’s built more housing and infrastructure than the other landlords, and keeps it all in good shape. Ms. Sly could, in theory, sit on her hands and just collect rent until someone’s house starts falling apart, after which she’d be required by law to intervene. She also has economic incentive to do the bare minimum.

As for the original population of Boxville, many are now homeless. Total rent (Land + property rent), even for the least productive land, is now well over 15 units per plot, at a baseline. In the early days of Boxville, total rent was 10 units per plot at a baseline, even for the best lands. For many, life in Boxville is far worse, despite the town’s incredible growth. Since land is necessary for all labor, and there is no more land to buy, Boxville’s landless residents are at a disadvantage to landowners no matter how hard they work. Plus, no one can build new affordable housing, such as apartments, on empty lots, because they’re already claimed.

Fixing The Crisis

Boxville’s progress has lead to wealth disparity and poverty, just like Henry George would have predicted. Now, how do we fix it?

Land Value Tax

The key lies in land rent. People are entitled to the fruits of their labor. Land ownership, by itself, produces nothing; it’s just a title. Therefore, it is unjust to demand the fruits of another’s labor over land ownership.

Henry George’s remedy is to tax as much land rent (Not property rent, land rent) as possible, to then fund government with the revenue, and to redistribute a portion of land rents equally among citizens. In a stateless society, the land rents would just be redistributed equally among citizens.

With a land value tax, all of society can benefit from increased land values, not just a few landlords. It is also meant to be a replacement (Or partial replacement) for other taxes, not an additional tax on top of existing ones. The goal is that, instead of paying both taxes and land rents, the land rents are the tax.

Normally, the land value tax would be applied very, very slowly over a few decades, to give society time to adjust. For the sake of brevity, we’ll apply it all at once, and see how Boxville’s situation changes.

The Absentees Are Out

With a high land value tax, doing nothing with land is just bleeding money. Mr. Fatcat must either sell or let go of his vacant plots, or else he’s losing money. No more sitting idly on empty land, waiting for it to rise in value, all the while keeping others from using it. The land’s rental value (Not the property rental value, just the land rental value) is now effectively zero, because any rent that could have been collected from it will be taxed away. This causes the sale price of land to trend to zero, the closer land rent is to 100%.

Due to the expenses of land value taxation, even though a land’s sale price might be low, only a productive member of society (Like the town’s many workers and business owners) would ever actually buy it. The collective owners of land C were productive from the start, and now they have every incentive to stay productive. Ms. Sly was fairly productive, actually providing some valuable services to her tenants. She may lose her land rent, but as long as she continues to provide value, she’ll be fine. She also has every incentive to be productive.

Mr. Fatcat and Mr. Moneybags, on the other hand, were less productive. Note what happens if they try to pass the land value tax onto their tenants. Their tenants can move. Land can’t. Even if every landlord raised their rents at the same time, they’d just cause people to live more densely (Or become homeless), and they’d still be liable for paying tax on their (Now slightly more vacant) lands! If either absentee landlord wants to get any rental income at all, they have to provide an actual valuable service. Otherwise, it’s in their best interest to sell their lands and leave Boxville alone.

Citizens’ Dividend

Let’s look at the Citizens’ Dividend, a universal basic income funded by the land value tax. Since communities, through their labor and social structures, give land its value, it only makes sense to return that value to them in some way. The Citizens’ Dividend takes a portion of the land value tax, and redistributes it evenly to every single citizen.

This is an indiscriminate and progressive redistribution scheme. It’s indiscriminate in that a millionaire will receive the exact same amount as someone who has nothing to their name. It’s progressive in that a small amount of extra money might mean the world to someone who is very poor, but it means almost nothing to the very rich.

With even a modest citizens’ dividend, no one would be too poor to eat. That seems like a much better use of land rent than filling Mr. Fatcat’s and Mr. Moneybags’ bank accounts to the brim with unearned wealth.

Conclusion

Poverty and wealth disparity appear to be perversely linked with progress.

Examples of this abound in the real world. Why are major urban hubs like San Francisco, New York, and Chicago rife with extreme poverty, despite the incredible wealth of those cities? Was this problem not predicted over a hundred years ago?

The story illustrated how this disparity occurs as land becomes more valuable, directly alongside technological, social, and population expansion. It also showed how, at the same time, increasing land values make a few people very, very rich, without lifting a finger. Most importantly, it showed how to fix this problem.

There are many aspects to Georgism that could not be covered in this brief introduction. If you have any questions about its practicality or implementation, please check out the resources below!