Introduction

Sociocracy represents a paradigm shift. It loosely means, “those who associate together, govern together.” That means that in a Sociocratic structure, a cashier is as much a part of governance as a CEO. How can this be? It is accomplished through several interconnected intentional systems, including:

We will explore these systems through a fictional fast food tale, in which a cashier saves the day.

Author’s Note

The following article is a high-level overview. To more deeply understand Sociocracy, the author highly recommends following it up with Sociocracy for All’s Sociocracy Journey.

Sociocracy was founded in the Netherlands, by an engineer named Gerard Endenburg. It has much broader implications than just the workplace, including the potential to reform global governance.

The Fast Food Fiasco

“Fantastic Fast Food” is a small fast food chain that has exploded in popularity. In the past year, the franchise has expanded from two, to four locations, with eighteen employees each. As the restaurant has grown in popularity, problems have arisen. Complaints from customers have been pouring in, of long wait times, poorly cooked orders, and general chaos when ordering food.

Workers, too, have been complaining. There is particular dissatisfaction among cashiers and cooks, where the turnover rate has reached an abysmal three months. If something is not done, and fast, the franchise is done for. Unsure how to proceed, “Fantastic Fast Food” CEO Woodsworth decides to try four different decision-making methods, across each of the four restaurant locations.

Decision Making

Decisions should be tolerable for everyone, even if they aren’t everyone’s preference.

Autocratic

In the first restaurant, an autocratic approach is tried. Woodsworth makes a decision on everyone’s behalf. Seeing that the cashiers are bearing the brunt of angry customers’ frustrations, Woodsworth promotes all part-time cashiers to full time. There are now eight full-time cashiers, split between two shifts. For the cooks, he mandates stricter quality controls.

The decision causes an uproar among restaurant staff. Several quit on the spot, and the ensuing day is more chaotic than ever. While it would be easy to lay the blame on the restaurant workers, Woodsworth digs deeper.

Democratic

The second restaurant votes on what decision will be made. A little over half the restaurant votes for increased pay, to compensate for workplace stress. The second most popular vote is for extra hires. There is much bickering between the two factions, since the restaurant cannot both increase pay and hire more workers at the same time. One lone voter, a cashier named Anna, writes in her own option: reduce the amount of cashiers at the registers. Since no one asked her opinion, no one understands why Anna wrote what she did.

The restaurant increases wages for all employees, but has to let a few go due to budget constraints. The now jobless workers are furious, the employees who wanted more hires are upset, and, worst of all, the restaurant is hardly less chaotic than before.

Consensus

A very different approach is taken for the third restaurant. In this restaurant, all eighteen workers, along with Woodsworth, have to agree to a decision before it is passed. The process is tedious, with each proposal sparking long debates and discussions. After hours of talking, a general consensus is reached, that there should be more help in the kitchen. The cooks are swamped with too many orders, and whenever an order is messed up, cashiers usually have to deal with the angry customers.

Most of the cooks want to hire an extra cook, but doing so would mean another employee (Most likely a cashier) would have to be let go, or reduced to part-time hours. None of the cashiers are fond of the decision. The restaurant’s workers have spent all day in their meeting, but could not come to a decision that everyone was pleased with.

Consent

Things are looking grim as the final restaurant prepares to meet. In this restaurant, decisions only pass when there are no objections. That means that, even if a policy isn’t everyone’s preference, it passes as long as it’s within everyone’s range of tolerance, and doesn’t interfere with the organization’s aim. Discussions proceed in a similar fashion to the third restaurant, until the idea of hiring an extra cook is brought up.

The cashiers voice their concerns. Ultimately, however, if the restaurant gets shut down, everyone will be without work. Begrudgingly, the cashiers acknowledge that they can tolerate cuts to working hours, or one of them leaving, if it means the restaurant will survive. A decision has been made, although between the nineteen present, it has taken most of the day.

Small, Decentralized Groups

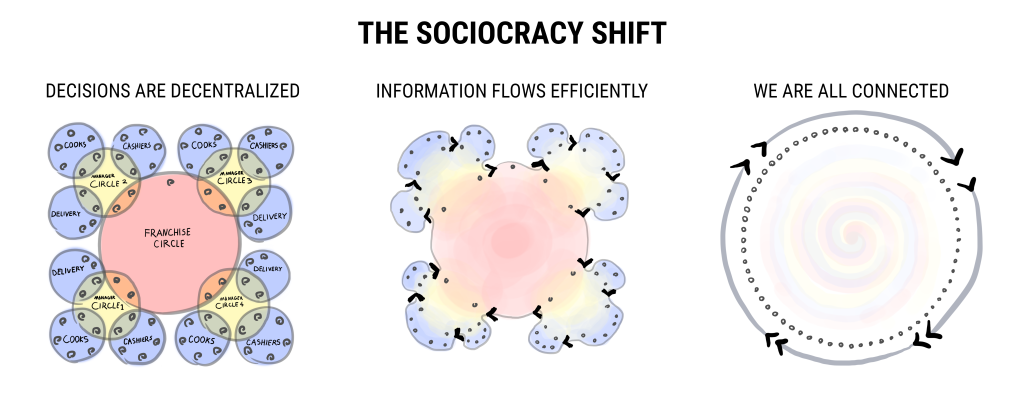

Groups should be kept to manageable sizes, and decisions should be made by the people they will affect.

As the meeting is about to adjourn, Bob, a cashier, speaks up.

“Whose hours will be reduced?” He asks.

A collective groan escapes from the workers. No one wants to launch another tiresome series of discussions. Once again, Bob speaks up.

“This decision really just concerns the cashiers. Why don’t we form our own group and discuss it among ourselves? Maybe everyone else can form their own groups, too.” Says Bob.

This proposal is readily consented to, and the restaurant splits into four groups. These groups are: six cashiers, six cooks, four delivery staff, and two managers. Mr. Woodsworth voluntarily leaves to check on the other restaurants. By reducing the discussion from nineteen to six people, the cashiers are better equipped to make a timely decision. Furthermore, the cashiers’ workload really isn’t the business of the restaurant’s cooks, or other staff.

Rounds

Everyone in a group should have a chance to speak.

The first few minutes of the cashiers’ meeting is heated, and frenzied. The loudest cashiers talk over each other in an effort to be heard, while the quieter cashiers don’t say anything. Bob waves his hands to silence everyone.

“I want to hear from everyone. Let’s all talk one at a time.” He says, after getting the group’s attention.

They proceed to speak one at a time, the loud cashiers reiterating their points from before, and the quiet ones offering a fresh perspective. The last cashier to speak is the quietest of them all, a shy woman named Amy. At first, she is hesitant to speak at all, but she relents after receiving encouragement from the group.

“We don’t have to fire or demote anyone.” She says, after a careful pause. “The cooks need more help in the kitchen, and more cashiers just means more orders. So why don’t we have some cashiers in the kitchen every now and then?”

The cashiers sit in stunned silence. Had they not given Amy the space she needed to speak, her solution may never have come up. In short order, all the cashiers consent to Amy’s proposal, electing to train a few select cashiers to also cook food.

Group Linking

Communication between groups ensures that everyone can be on the same page.

Bob relays Amy’s proposal to one of the restaurant’s managers.

“This is great.” She says, “But it will affect the cooks. Let’s make sure we’re all on the same page.”

So, the manager gathers representatives from each of the restaurant’s groups. Two cashiers (Bob and Amy), two cooks, two delivery staff, and two managers form a “Manager’s Circle.” Rather than the managers making decisions on everyone’s behalf in an autocratic fashion, decisions that affect the entire restaurant will be consented to in the manager’s circle.

Amy’s proposal is consented to in the manager’s circle, then relayed to the cooks’ group, where it is also consented to. By having representatives from each group in the manager’s circle, information can quickly be shared across the entire restaurant, despite all the workers not meeting at the same time, all at once. This allows quick decision-making, that is still consensual.

Aftermath

The fourth restaurant spends the following day training four cashiers in the kitchen. The next day, the strategy proves a resounding success. Whenever the cooks feel overwhelmed with orders, a cashier moves from the registers to the kitchen, reducing order inflow, and speeding up the cooking. The restaurant’s decision-making methods are adopted at every branch, and refined over time.

Two members from each restaurant’s management circle join Mr. Woodsworth to form a “Franchise Circle,” where decisions about the “Fantastic Fast Food” franchise’s future are made with the consent of the group. Eventually, with work distributed more efficiently than ever across small, decentralized and linked groups, the franchise’s pay structure begins to flatten, ensuring that everyone shares in the success of the organization.

That’s the story of how a cashier saved a franchise. Remember, we all matter, and we’re all connected. Let’s build from a foundation of love and cooperation, not fear and control.

Resources

Education

- Sociocracy For All, a Sociocratically run nonprofit bringing Sociocracy to the World:

- The Sociocracy Journey, a great starting point for learning about Sociocracy:

Sociocracy in Practice

- Where is Sociocracy being practiced?

- Sociocracy case studies:

- Sociocracy has broader implications than just the workplace:

Miscellaneous

- The real life story that inspired “The Fast Food Fiasco”:

Community

- The Humano Ludens Discord community: